Long-term investment trends in our in car industry, pharmaceuticals and North Sea oil and gas are the main factors depressing UK export performance

A comprehensive sector-by-sector analysis of UK trade explodes the myth peddled by many commentators that the post-pandemic downturn in exports to the EU can be traced to Brexit.

An apparent consensus has emerged in recent months that Britain’s formal 2020 departure from the European Union has proved damaging to UK exports as the country has recovered more slowly than other G7 countries since the pandemic.

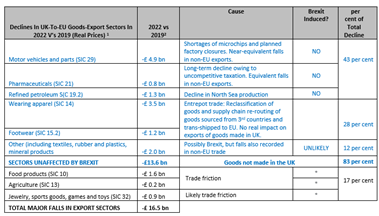

But the new study from the Centre for Brexit Policy, drawing on the latest trade figures, concludes that a combination of global factors and the distinctive pattern of UK exports explains almost all of the current shortfall in exports.

A heavy reliance on overseas sales of cars and aircraft components plus cutbacks in North Sea oil and gas production are the mains reasons why the UK performance in goods exports has lagged behind its international competitors.

The report observes that more than 80 per cent of the UK’s current shortfall in exports is in sectors where current export levels cannot in any meaningful way be ascribed to the UK’s exit from the European Union.

The report, Coincidence is not Causation: Why Brexit is Not the Cause of Lower Goods Exports to the EU, by trade analyst Phil Radford, concludes:

“The UK’s particular mix of exports explains why UK trade was bound to underperform G7 countres in 2021 and 2022.”

“The motor vehicle and aerospace sectors are easily our biggest goods-export industries in global terms. In 2019, for example, they delivered more than 20 per cent of all UK goods exports.”

Yet this sectoral study shows that in the UK, these two sectors were easily the hardest hit by recent global events, including the pandemic, microchip shortages and the temporary collapse of civilian aviation. In G7 terms, this made UK trade uniquely vulnerable to global events.

The sectoral analysis also shows how meanwhile UK exports missed out on recent surges in global demand.

Declining long-term investment in the North Sea meant our trade did not benefit from the energy crisis, as happened in the US and Canada. Meanwhile, the offshoring in our pharmaceutical industry meant we failed to gain from the spike in demand for vaccines, like Germany and the US.

The report shows how Brexit has had a “trivial” effect on UK-EU trade compared to other impacts that result from failures to address long-term challenges to UK trade. It urges policy changes in critical sectors of the economy, notably pharmaceuticals (hit by high corporate taxes), motor vehicles (damaged by subsidies within the EU) and energy (green policies have made us a huge importer of energy).

Mr Radford highlights three areas of prime concern.

- Pharmaceuticals. The £10.3 bn UK–EU deficit in trade in pharmaceuticals is more than double the £4.8 bn shortfall in UK goods exports to the EU that can be definitely or probably attributed to Brexit.

- Motor vehicles. The £30.2 bn deficit in UK–EU trade in motor vehicles is almost double the entire £16.5 bn shortfall in exports to the EU that result from all causes.

- Energy. The £55 billion net trade deficit in energy we sustained in 2022 overshadows every other negative number in UK–EU trade. It is 20 times greater than the definite £2.7 billion Brexit impact identified in this sectoral analysis.

Mr Radford comments:

“The UK–EU deficits in these three sectors are the result of policy choices by UK governments, and not shifts in global competitive advantage.

“Their impact on UK trade is multiple times worse than the impacts of Brexit on UK’s food, agriculture, jewellery and other sectors. And yet the challenges faced by the UK’s auto and pharma sectors in particular receive next-to-zero attention from British trade commentators.”

ENDS

Click here to read the report in full.